FACT VERSUS FICTION

My

books are based on what archaeology and history tell us about the time

and place in which they are set. However, while I have stuck to the

facts if they are known and accepted, there is much that we don’t know,

or which is the subject of debate among scholars. In these cases, I

have proposed things based on Celtic evidence elsewhere, or common

sense. At other times the story itself takes precedence.

My

books are based on what archaeology and history tell us about the time

and place in which they are set. However, while I have stuck to the

facts if they are known and accepted, there is much that we don’t know,

or which is the subject of debate among scholars. In these cases, I

have proposed things based on Celtic evidence elsewhere, or common

sense. At other times the story itself takes precedence.

The Dalriada trilogy is based on known history of the late Iron Age and Roman period in Britain. The Irish series is based on myths. However, I have grounded them in the Iron Age archaeology of Ireland and other Iron Age sites in Britain and central Europe

The Swan Maiden and The Raven Queen»The Dalriada Trilogy »

THE SWAN MAIDEN AND THE RAVEN QUEEN

- The Ulster Cycle

- History of the Tale

- A Window on the Iron Age?

- Glimpses of History and Archaeology

- Places

The Swan Maiden is based upon the old Irish tale of Deirdre and Naisi. However, Queen Maeve, or Medb, does not have a single, coherent ancient story to her name, so The Raven Queen is a "re-imagining" of her life using scraps of various myths - primarily the famous tale of The Táin, or The Cattle Raid of Cooley. I highly recommend reading the original myths. For both SM and RQ I used Thomas Kinsella’s book The Táin (Oxford University Press, 1969). For the latter part of The Swan Maiden I used Lady Gregory’s Cuchulain of Muirthemne (reprinted, Gerrards Cross, 1970).

The text of Lady Gregory’s book can be seen at http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/cuch/lgc10.htm Go to the chapter on “The Fate of the Sons of Usnach”.

The version of Deirdre and Naisi that Kinsella used from the ancient Book of Leinster can be seen at: http://www.maryjones.us/ctexts/usnech.html. If the page has changed, go to Mary Jones’s site at http://www.maryjones.us/ and look under Celtic Lit; Irish texts; the Book of Leinster; and the section “The Exile of the Sons of Usnech”.

At Mary’s site you can also find the full text of the Táin Bó Cúailnge, The Cattle Raid of Cooley, upon which I based the major part of The Raven Queen's plot. Other versions are all over the web.

The Ulster Cycle

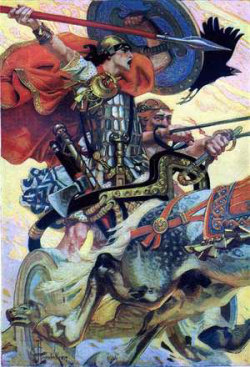

Cuchulainn Rides His Chariot Into Battle

by J. C. Leyendecker

The Ulster Cycle revolves around the exploits of King Conchobor (anglicized as Conor) and his Red Branch warriors, including the famous Irish hero Cúchulainn. The Táin describes a war between Queen Maeve of Connacht and Conchobor over a famous bull.

Central to the story of The Táin is the defection of a large number of Red Branch warriors, led by Fergus mac Roy, from the Ulster side to the Connacht side. The tale of Deirdre, as set out in The Swan Maiden, appears to be a foretale that explains this defection. The consequences of this event go on to drive the plot of The Raven Queen.

History of the Tales

The historical background to these stories is confusing. The early peoples of Ireland were not literate, and before Christianity the tales were passed on orally by bards. Nothing would have been written down until after the coming of Christianity in the fifth century, but the earliest surviving manuscripts were made in medieval monasteries much later even than that.

Thomas Kinsella takes his Deirdre translation from the twelfth-century text the Book of Leinster, although the language of the prose sections dates them to the eighth or ninth century, and the verse sections seem to be a century or two older. Further than this, we are stretching back into the mists of time and bard tales.

I have mainly followed Kinsella’s sparse sixth-to-ninth century version of the Deirdre story. However, from the time that Conor’s envoys are sent to retrieve the fugitives, I switched to a later fifteenth-century version of the tale. This was found in the Glen Massan manuscript, discovered in Scotland - for Scotland also lays claim to the Deirdre story.

This later version was used by Lady Gregory in her retelling of the Táin Cuchulain of Muirthemne (reprinted, Gerrards Cross, 1970), which embroiders the story with much more detail.

A Window on the Iron Age?

A typical Celtic roundouse at

Flag Fen Archaeology Park

Since they were transcribed by Christian monks, no one really knows how faithfully these Celtic pagan stories were captured, and whether the bias of the writers and the society in which they lived — twelfth-century Ireland — meant that events have been changed, or even left out. Is this why the beautiful maiden Deirdre and the fiery Queen Maeve are both scorned in the original myths as being manipulative, selfish, outspoken women, possessing frightening sexual powers over men? We will never know.

Glimpses of History and Archaeology

The Vix krater, used to serve wine at feasts

There were no historical events to follow, but I have tried to ground them in the archaeology of Ireland, Britain and Gaul and the writings of the Romans and Greeks about Celtic weapons, dress, food and houses.

Many of the aspects of these Irish tales — the feasting, cattle raiding, boastfulness and courage of the warriors, single combat of champions, taking of enemy heads, riding in chariots — also fit in with what these Roman and Greek writers observed about the Celts.

In turn, archaeological finds from western Europe dated to this time back up some of the elements of the tales. Great cauldrons and drinking vessels, evidence of the importation of wine, and pits of animal bones suggest large-scale feasting was a part of Celtic life.

Finely-decorated horse

harness fittings from the UK

Jewellery is of fine and highly-skilled workmanship, and the amount of gold, other metals and enamel used suggest they were enthusiastic displayers of wealth. This fits in with the showy, boastful warrior culture described in the Irish myths.

Celtic art confirms the importance of the taking and displaying of enemy skulls, and the cult of the head.

The four sacred festivals of Imbolc, Beltaine, Lughnasa and Samhain appear in the myths, as well as being mentioned in other contemporary writings. A bronze “calendar” found in Coligny in France dating to this period mentions Beltaine and Lughnasa, as well as focusing on Samhain. This is important, as it is rare evidence of religious beliefs.

Neck torcs excavated from Erstfeld, Switzerland

Evidence from Irish bog bodies suggests that warriors stiffened their hair with a paste made from pine resin and herbs imported from the Continent: I could not resist that one!

In Ireland, Iron Age trackways have been found, constructed of oak planks stretched across bogs, larger than would be needed for foot traffic. They seem to be “roads” for carts and horses, but could they also be for nobles in their chariots?

The Irish myths speak of the heroes driving in chariots. They have never been found in Ireland, but they are known from Iron Age graves in England, France, and Switzerland.

There are other differences between the stories and what has been excavated in Ireland.

The Desborough Mirror from

Northampton, UK decorated

in the ornate La Tene style

However, bear in mind that only a tiny percentage of Celtic artifacts have come down the years to us. For us to possess them now, they first had to be buried or lost (not destroyed or melted down); then survived acid soils, ploughing, the digging of trenches for houses and drainage, and destruction by rain and rivers for two thousand years. Then, they had to be found again.

We know so little, and most things that perish, such as wood, leather and cloth, will have disappeared.

Since we know the Celts had wide trading networks, and since the surviving art and jewellery is so ornate, hinting at skilled craftsmen and wealthy nobles, in my novels I have always described the life of my ruling elite as very luxurious.

La Tene style sword, mid-1st century BC

If the Celts were so in love with decoration that they spent all that time on bridle fittings for their horses, or on crafting an exquisite handle for a simple jug, I am sure they also enjoyed decorating their houses, bodies, hair and clothes to the same degree. Unfortunately, all of these have rotted away. Mostly only the cold metal survives.

For a good photo collection of other Celtic artifacts, visit the www.sheshen-eceni.co.uk site.

Places

Glen Etive: the traditional Scottish

home of Deirdre and Naisi

The Swan Maiden characters also visit Dunadd, the enigmatic Celtic fort in the Kilmartin valley, south of Oban in Argyll.

King Conor's fort of Emain Macha in Ireland has been identified as the present-day site of Navan Fort, near Armagh. There is a wonderful museum there all about the Ulster Cycle of tales, and you can sit in a real roundhouse and listen to them!

In The Raven Queen, Maeve’s stronghold of Cruachan has been identified as Rathcroghan near Tulsk, Roscommon. Dun Ailinne is still the name of the modern site, and the Hill of Uisneach is supposedly sacred because it is in the center of Ireland. The characters also visit the island of Inish Mor, in Galway, and the site of the great Iron Age fort of Dun Aengus. The final battle is fought beneath the slopes of Slieve Gullion, traditionally associated with the great Irish warrior Cuchulainn.

DALRIADA TRILOGY

- THE WHITE MARE AND THE DAWN STAG

- The Roman Campaign

- Dalriada

- Dunadd

- People

- Language

- The Sacred Isle

- The Female Royal Line

- The Sisterhood

- Herb Use

- The Rye Fungus

- Tribes

- Names

- Gods & Godesses

- Standing Stones/Mounds

- Pictish Symbols

- Places in The White Mare

- Places in The Dawn Stag

- Interesting facts from The Dawn Stag

- THE BOAR STONE/THE SONG OF THE NORTH

- The Great Barbarian Conspiracy

- So what happened after the end of the book?

- The End of Rome in Britain

- Interesting Facts from The Boar Stone/The Song of the North

These books are mostly set around the Kilmartin valley in Argyll, Scotland. There you can visit the hillfort of Dunadd, and the line of “ancestor” mounds, tombs and stone circles. Other places important in the stories are referenced below.

Temple Wood stone circle, Kilmartin

THE WHITE MARE AND THE DAWN STAG

The Roman campaigns

The basic information about the Roman governor Agricola’s campaign in Scotland from 79 to 83 AD is taken from the biography that his famous historian son-in-law Tacitus later wrote. However, his account is sketchy in places, and I have made small changes to fit my story.

Although I had already worked out the basic plot of The White Mare before I read Tacitus, he says that early in his campaigns, Agricola entertained an exiled Irish prince, and was thinking of invading Ireland. I used this by having Agricola tempt my Irish hero Eremon to defect to the Roman side. The following relate to events in The Dawn Stag.

AD 81 - Tacitus says that this year Agricola ‘crossed (water) in the leading ship’ and subdued unknown peoples, drawing up his troops facing Ireland. Gordon S. Maxwell notes that scholars have long debated what this section of Tacitus means. In The Romans in Scotland (1989) he suggests the translation could be re-interpreted thus: the Roman army did not cross water at this time but the “trackless wastes” and moors of Galloway in south-west Scotland. I took this idea and on it based Eremon’s first campaign among the Novantae. It should be noted that many scholars think this actually means Agricola crossed the Clyde and campaigned closer to Epidii lands.

AD 82 – Tacitus says this year began with an uprising of the tribes north of the Forth, who did attack several forts. While the detail of Lucius’s campaign up the east coast is my own, Agricola did split his forces, which encouraged a surprise night attack on the Ninth Legion by the enemy. A. R. Birley’s translation of Tacitus’s text Agricola uses the words: ‘They cut down the sentries and burst into the sleeping camp, creating panic.’ Tacitus states that Agricola came to the rescue just in time, but I made the Albans victorious instead. Tacitus was eulogising his father-in-law, and it is quite possible that any Roman defeats were played down or omitted. This year, Agricola’s wife did bear him a son.

AD 83 - In the spring, Agricola’s infant son died. Tacitus infers that his grief was buried in a renewed determination for conquest. The Roman army met the tribes at a place called ‘Mons Graupius’, where the tribes had drawn up a force of 30,000 men. We don’t know exactly where Mons Graupius was, but the prominent hill of Bennachie near Aberdeen is one good contender, particularly as nearby is the large Roman matching camp at Logie Durno. Tacitus reports the battle occurring at the "end of the season" but I moved it to summer. The leader of the Scottish forces was called Calgacus, which means something like “the swordsman.” I followed Tacitus for the rough format of the battle — and Agricola did use cavalry reserves. I won’t spoil the ending!

Dalriada

Dunadd fort in Kilmartin, Scotland

Regardless, Dark Age Christian sources report that the Gaelic Dalriadan kings, with their seat at the fort of Dunadd in Argyll, warred with the Pictish kings in the east of Scotland for many years. In 843 AD, the two peoples were joined by the accession of the Dalriadan king Kenneth MacAlpin to the Pictish throne, a man who was possibly descended from the Pictish royal line through his mother. After this, the Picts seem to disappear as a separate people from history, and Gaelic became the language of Scotland, and Gaelic kings its rulers.

Most scholars do agree that, because of their close coastlines, the northern Irish were probably in contact with western Scotland centuries before the accepted “colonization”.

So the first mixing could easily have occurred in the first century, as occurs in my books with the arrival of a few nobles and the intermarriages of the main characters. A note of interest from The Dawn Stag: my characters Conaire and Caitlin have a son called Gabran. Gabran was a documented king at Dunadd, though he lived later than Conaire’s son.

Dunadd

The carved footprint on top of Dunadd,

supposedly used for the inaugurations of kings

People

The term ‘Pict’ was not used by Roman writers for the peoples of Scotland until the fourth century, and may come from a Roman term meaning ‘painted people’ — possibly because they tattooed themselves. However, although my Scottish characters obviously ‘became’ the Picts we don’t know what they called themselves, and so I’ve fallen back on an old name for Scotland — Alba — and called them Albans.

With regard to the “Gaels”, there is evidence that this is what the early peoples of Scotland called those in Ireland, and what the Picts called the Gaelic-speaking people living in the west of Scotland after 500 AD.

Argyll, where the people of Dalriada had their later center of power, means “Coast of the Gael.”

Language

By the sixth century AD there is evidence that the Picts (descendants of the native Scottish people) and the Argyll Scots (possibly descendants or relations of the Dalriadan Irish) spoke a mutually unintelligible form of the Celtic languages. However, languages can change rapidly, and we don’t know how close the two were earlier in history. I’ve left them essentially speaking the same language, for simplicity.

The Sacred Isle

The stones of Callanish, Isle of Lewis

The Female Royal Line

One of the most intriguing aspects of the Picts is that there is some tenuous suggestion that royal blood was passed through the female line, rather than from father to son. For example, in the list of Pictish kings which states their fathers' names, no son ever succeeds his father to the throne. In a matrilineal system, men would succeed their uncles, brothers, and grandfathers instead. If true, this puts the early Scottish peoples out of step with what we know of the early Irish and British. This idea was one of the starting points of my story.

The Sisterhood

Following on from the idea of the female royal line, I began to muse that such a veneration of female blood and power could stem from an ancient form of Mother Goddess worship, surviving in Scotland from the Neolithic age, or even earlier. In my books, this female-centered religion of the “Old Ones” involves an order of priestesses: the Sisters.

The existence of druids is attested by Classical writers — however, I am aware there is no evidence for a goddess-worshipping sisterhood. It is purely fiction (unfortunately!).

Herb Use

With some simple research, anyone can discover the medicinal properties of British native plants. Untrained use of such preparations can be, of course, very dangerous, and I do not advocate that anyone try them. Many plants have psychoactive properties, and some people believe the druids used such plants in their rites. For safety reasons I didn’t detail what my herbal preparation saor might have contained, for many plants could have produced this “out of body” effect.

Likewise, the ancient peoples knew of both contraceptive herbs, and those which could produce abortions; I haven’t named them. The Romans apparently over-used one contraceptive plant to the extent it became extinct.

The Rye Fungus

The ergot fungus grows on rye plants under certain conditions. It contains psychoactive compounds that some scholars think may have caused the effects attributed to witches during the Middle Ages — uncontrollable twitching and fitting, hallucinations, and a burning sensation in the extremities and tongue. There has been occasional suggestions that it was ritually used by ancient peoples. It is extremely toxic, and ingestion is usually fatal. Its use in my books is purely fictional.

Tribes

The names of the tribes on my maps are taken from a text by the Greek geographer Ptolemy, writing in the second century AD. It shows the placements of major tribes in Great Britain and Ireland. It is possible that this information was captured during Agricola’s campaigns, or even earlier.

Some people think the tribal names relate to animals, and could indicate totemic affinities. Thus the Epidii might be related to horses, and the Lugi to ravens (which is why the Lugi king has a raven sail). A note on the Caledonii: On Ptolemy’s map, this tribe is shown as the Caledones. However, by the fourth century, when the last book in this trilogy is set, the name seems to have become “Caledonii” to Roman writers, so for simplicity’s sake I’ve used that.

Names

I don’t follow one naming scheme, since we don’t know what language the Albans spoke: was it closer to Welsh or Irish at this time? So some of my names are Irish, some Pictish, and some invented. We have a list of later Pictish kings: I’ve used names from this list for major male characters including Maelchon, Gelert, and Nectan. We don’t have records of female Pictish names, so these are mostly Irish or invented.

The exception is Calgacus, which means something like “The Swordsman.” Tacitus names him as having lead the resistance of the tribes against Agricola’s armies at Mons Graupius.

Rhiann, though based on Welsh, is not a traditional name. All of Eremon’s men have Irish names, although Eremon is a mythical name — the first Gaelic king of Ireland.

Gods and Goddesses

A goddess from the Gundestrup Cauldron

Standing Stones / Mounds

All of the standing stone arrangements and tomb mounds in the United Kingdom were built by Neolithic or Bronze Age peoples before 1500 BC, not by Celtic Iron Age peoples in the first century AD. However, the Celts probably venerated and possibly used older monuments for their own rites. Though there is evidence for this in other parts of Scotland, there is no evidence for it in the Kilmartin valley, or at Callanish on the Isle of Lewis.

Pictish Symbols

The Picts left behind extraordinary carved stones dating from the sixth or seventh century AD onwards, so I had the idea that the same symbols were used to decorate wood, walls and bodies much earlier. The symbols used for my chapter headings are Pictish symbols, as seen on the later stones. The body tattoos I mention are based on Pictish carvings of bears, boars, stags and eagles.

At Dunadd there is a famous later Pictish carving of a boar, and as my Dalriadic line began with my heroes Eremon and Conaire from the first two books, I gave them this boar as their totem.

The main symbol I mention in the book is called the "crescent and V rod" (see left).

The main symbol I mention in the book is called the "crescent and V rod" (see left).

This is the one I describe as being the crescent of the moon goddess, representing the feminine; crossed by a spear or arrow, representing the masculine. People have asked me if this is its real meaning — unfortunately, no one has any idea what the Pictish symbols mean. This came to me as an intuition, and fitted my book, so I used it.

Places in The White Mare

Castle Dounie

My Dun of the Cliffs is an Iron Age fort near Crinan now called Castle Dounie; climb up there for a spectacular view of the Sound of Jura.

Calgacus’s Dun of the Waves is an invention, sited near present day Inverness.

The existing hillfort of Traprain Law, near Edinburgh, is the home of the character of Samana.

The Leven river that flows from Loch Lomond probably means the Elm River, as I name it. Lomond probably means “beacon” so the Loch of the Beacon is Loch Lomond, and The Beacon is the mountain Ben Lomond.

The Clyde was known in Greek and Roman times as the Clutha.

Places in The Dawn Stag

Achnabreck carvings, Kilmartin

The stone circle she visits with Linnet is Temple Wood (see above), and the standing stones among which she says her farewell to Linnet before the last battle are the Nether Largie stones; all in Kilmartin valley.

The moor the priestesses cross is Rannoch Moor.

It is Loch Tay on the other side, which is well known for the remains of its crannogs — man-made island forts. There is a reconstructed crannog there, which inspired the dun at which Rhiann tells her tale.

Nether Largie Stones, Kilmartin

The sacred mountain of Argyll is Cruachan, and it lies at the head of Loch Awe, which means something like “loch of the waters”, as I name it.

This loch does lead to the Kilmartin valley, and Dunadd.

Interesting facts from The Dawn Stag

Since stirrups were not invented until much later, ancient cavalry saddles probably had leather horns to grip the rider’s leg, and enable him to brace and swing a sword.

Wheat and barley were stored in clay-lined pits, and the fermenting grains on the damp edges used up all the oxygen and produced carbon dioxide, which together kept the grain fresh.

Reconstructed saddle by Peter Connolly

In the Irish myths, bards were feared for their abilities to shame even kings into changing their behaviour.

Tacitus says the Celts at Mons Graupius did use chariots.

The glimpse Rhiann has the night before battle, of Romans swimming across a strait, refers to the sacking of the druid sanctuary of Anglesey off the coast of Wales in AD 60.

The woman hiding with her child from falling iron bolts recalls the Roman destruction of the great hillfort of Maiden Castle in Dorset, soon after the Roman invasion of Britain in AD 43. Skeletons were found here with Roman ballista bolts embedded in their spines.

The snippet of song at the end is adapted from the Irish myth of Deirdre as she leaves Alba to return to Erin.

THE BOAR STONE (UK) / THE SONG OF THE NORTH (U.S)

AD 366 – AD 367

In the first two books in the trilogy, the first Irishmen (Gaels) come from Dalriada in Ulster and intermarry into an early Scottish tribe (Picts). By the time of the third book, The Boar Stone / Song of the North, the Gaels of Irish descent, living at Dunadd, have become the enemies of the Pictish tribes that inhabit the rest of Scotland. To their south is Hadrian's Wall, manned by Roman soldiers as a border between the barbarian lands of Scotland and the Roman province of Britannia (modern-day England, roughly speaking).

The Great “Barbarian Conspiracy” Of 367 AD

Housesteads Fort on Hadrian's Wall,

the border between Roman England

and the wilds of barbarian Scotland

Though there had been previous raids by the Picts and Scots, most notably in 360 AD, nothing like this had been unleashed on Britain before, and was distinguished by the uncharacteristic co-operation of the barbarians involved.

There were indeed scouts and spies — the areani — that roamed north of Hadrian's Wall and were quartered in the outpost forts, and at this juncture they were apparently lured by bribes to turn traitor to the Roman administration, providing information to the enemy which aided their attacks.

Fullofaudes, the Dux Britanniarum, was surprised, cut off and “overcome”; Nectaridus, the Count of the Saxon Shore, was slaughtered in battle. The barbarian hordes, according to Ammianus Marcellinus, penetrated deep into the south-east of England and caused havoc, breaking into small bands to plunder the rich villas and undefended towns.

At the same time the order of the Roman army had completely disintegrated, with the cohesion of units destroyed, and leaderless bands of soldiers roaming at will.

Ammianus is not without his sceptics, as he was writing at a later time and probably seeking to glorify the man who came to put down the rebellion. But though there is little archaeological proof, there are various pieces of circumstantial textual evidence to suggest his report could be accurate.

So what happened after the end of the book?

According to Ammianus Marcellinus, a commander called Count Theodosius was despatched by the emperor Valentinian I from Germany with a field army of crack troops to restore order. Over the next two years he defeated the roaming bands of barbarians with their plunder, fortified towns and regarrisoned many forts on Hadrian’s Wall.

But despite this, the outpost forts north of the Wall were abandoned, the areani spies and scouts disbanded, and all Roman control over the borderlands was relinquished: the Romans had indeed left Alba.

The End of Rome In Britain

A milecastle on Hadrian's Wall

Again and again, British soldiers were withdrawn from the frontier to shore up defences in Gaul, Germany or Italy, and in 383 AD an upstart senior British officer, Magnus Maximus, declared himself western emperor, supported by the British forces and nobility.

When he left to fight for his throne in the east he took a large army with him, but after his defeat by the eastern emperor those troops never came back.

By the early 400’s the emperors had their hands full trying to defend themselves against the Goths in the east. The province of Britannia was denuded of troops, and after 402 there is little trace of coins, so it appears the money dried up, too, with no pay for soldiers or officials.

Another would-be British emperor, Constantine III, left Britain in 407 to defeat more barbarian invaders and usurp the western throne. He probably took the last remaining regular troops with him.

According to other historians, Britain came under attack from the Saxons around 410, and after appeals by the British nobility to the Emperor Honorius for help, they were told to look to their own defences. The British towns and tribes reverted to ruling themselves.

So the withdrawal and disintegration of the organised army and the end to centralised Roman government in Britain was a gradual change, rather than a sudden recall. The evidence at Hadrian’s Wall is of a gradual abandonment at some forts, and at others occupation continues, albeit in a more basic form, with people scratching a living among the stone buildings.

Disease and desertion would have taken its toll on the remaining garrisons, and eventually the few soldiers that stayed on must have settled down to farm, being absorbed into the local population.

By 410 AD Britain had therefore ceased to be part of the Roman Empire and was left to its own fate. A century later, the first waves of Saxons, Angles and Jutes were to change its face forever.

Interesting facts from The Boar Stone / The Song of the North

Tutors to the Roman nobility were often slaves, so Minna’s acceptance as such at Dunadd was not unusual. Furthermore, some slaves could attain a high status, and many were freed by their masters, some of their descendants rising to dizzy heights in society.

The north of Britain does have native poppies — the “red flower” — and even though the local species is not as potent as the more well-known eastern opium poppy, it does contain natural opiates that could be concentrated to effect sedation.

Some plant poisons were used on blades in the ancient world, and though many come from the Mediterranean they could easily be imported into Britain. A noted one was wolf’s-bane, as it was used on the barbs of arrows to kill wolves. Better known as aconite, it is extremely dangerous and damages the heart muscle, causing a fast pulse and shallow breathing, and swift death if ingested orally.

Rights queries: Russell Galen

at Scovil Galen Ghosh Literary Agency

Publicity queries: Kathleen Rudkin

at Bantam Dell